If you know anything about the history of how the Thoroughbred came into existence, you might have heard about the three foundation stallions – the Byerley Turk, the Darley Arabian, and the Godolphin Arabian.

In Part 2 of this 3 part series we’ll take a look at those three foundation stallions and how, when bred together with native English mares, they gave way to a new breed: the Thoroughbred.

To catch up on Part 1, History of the Thoroughbred: Racing Before the Breed For Speed, click here.

The Three Thoroughbred Foundation Stallions

While horse racing was just getting organized in England, knights were also returning to Great Britain from the Crusades during the 11th and 12th centuries, often telling stories about the speed and endurance of horses from “The Orient.” These horses, predominately Arabs or Turkoman, were famed for their speed, agility, endurance, and conformation, eventually leading to their import to England and Ireland to help improve the bloodlines and racing competitiveness of native stock.

In this video below, produced by CNN in 2016, a visit to the National Racing Museum in Newmarket, England, discusses the early beginnings of Thoroughbred breeding.

Without too many spoilers, let’s take a closer look at each of these horses, why were imported and what happened to their breeding lines.

The Byerley Turk

The first of the imported foundation stallions received his name from an entry in the General Stud Book, one of the earliest books of record for breeding and importing horses in England and Ireland that is published every 4 years and continues today. In the General Stud Book he was referred to simply as the “Byerley Turk, was Captain Byerley’s charger in Ireland, in King William’s wars (1689).” He was noted in those records as a large dark brown, nearly black stallion with exceptional speed.

The details prior to the Byerley Turk’s military service in Ireland are largely speculative. One theory claims the horse was one of three stallions captured from a Turkish officer during the 1688 Battle of Buda in Hungary, while others claim he may have been captured at the Battle of Vienna or even bred and born in England from other captured Turkish stallions.

Regardless of his provenance, Captain Byerley took ownership of the horse as early as 1688, thus the name that he became famous for, the Byerley Turk.

The stud and the Captain were deployed to Ireland in 1689 during King William’s War where they served together with distinction from 1689-1690 and the Captain was promoted to Colonel. In some early records it’s noted that “at the Battle of the Boyne [the Captain] was so far ahead of reconnoitering the enemy that he narrowly escaped capture, owing his safety to the superior speed of his horse.”

When Colonel Byerley retired from the military in 1692 he married his cousin, Mary Wharton, a wealthy heiress from North Yorkshire, England. They moved to her family estate at Goldsborough Hall near Knaresborough, North Yorkshire, while the horse retired to stud, first at Middridge Grange and then later at Goldsborough Hall where he died there in 1706 and is believed to be buried.

The Byerley Turk left behind a long legacy of progeny that is only reaching the end of production today. Some of his most productive sons were Jigg (born 1701), who became the sire of Partner, who in turn sired Tartar, who in turn sired Herod in 1738. Herod produced one of three sire lines from which all modern Thoroughbreds descend today. He also sired a productive racehorse, Basto (born 1704) who won a number of match races from 1708-1710, along with a number of productive mares.

While most branches of the Byerley Turk’s line have died out, the line persisted with the production of a major sire every few generations.

The darley Arabian

The Darley Arabian was the second of the imported foundation stallions who went on to become perhaps the most well-known and prolific sire of the three. He is also the stallion we know the most about.

Born in Aleppo, Syria, on January 4, 1700, this colt was bred and sold by Sheik Mirza II to Thomas Darley, a wealthy Englishman and member of the British Consult to then Queen Anne, as a four year old in 1704. Darley’s father owned a stud farm at Aldby Park in England and Thomas made it his mission to find a perfect Arab stallion to add to their farm.

In Darley’s own words the horse “was immediately striking owing to his handsome appearance and exceedingly elegant carriage” and stood a then tall 15 hands high. Darley acquired the horse after trading the Sheik for a shipment of rifles and 300 gold sovereigns. By some accounts the Sheik later tried to back out of the deal, perhaps realizing what a promising horse he’d traded away, but Darley kept the colt and left for Ireland over the next 5 months at sea without port.

The same year that Thomas Darley acquired the Arabian he also passed away, allegedly due to poisoning on the way to his wedding. The Arabian was sent to stud at Aldby Park under the care of Darley’s brother by marriage, John Brewster Darley.

Although the Darley Arabian never raced he was an incredibly influential sire despite only breeding with Darley’s own mares between 1705 and 1719. He lived to be 30 years old and died in 1730. Today, 95% of all modern thoroughbreds can trace their Y chromosome back to this stallion.

The Darley Arabian foaled Bartlett’s Childers, the great-grandfather of Eclipse, a prolific racehorse born in 1764. Eclipse was an unruly colt but an exceptional racehorse, winning 18 races and inspiring the phrase, “Eclipse first, the rest nowhere.” He was said to have near perfect conformation with one unexpected characteristic — an abnormally large heart. This enlarged muscle gives a horse greater stamina and strength and is said to be a common characteristic of racing legends like Secretariat and Phar Lap.

Eclipse was in turn a prolific sire at stud, producing two sons Pot8os and King Fergus who produced a number of winning offspring.

This article in Populous Magazine, originally published in 2016, discusses the Darley Arabian’s line in detail through Eclipse, Stockwell, Nearco, and Northern Dancer. The Darley Arabian and Eclipse line have also produced Triple Crown winner’s American Pharoah and Secretariat.

The Godolphin Arabian

The Godolphin Arabian’s story of prominence was supposedly an unlikely one. Foaled in Yemen sometime around 1724, the Godolphin Arabian was shipped from Syria to Tunis before being given to the King Louis XV of France as a gift or part of a gift from the Emperor of Morocco. While little factual evidence can be found to support or deny it, some accounts claim the King cared so little about the horse that he was eventually used to pull a water cart through the streets of Paris.

Whether or not his history is as fairy-tale-like as some children’s books may have made it, in 1729 he was spotted by Edward Coke, an Englishman with connections in France, particularly with the Duke of Lorraine with whom he is said to have worked a deal to bring the Godolphin Arabian back to England.

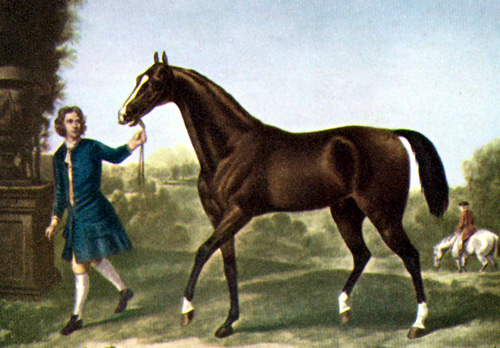

The Godolphin Arabian was a headstrong, small, brown bay with a large crest in his neck that was noted in many of his paintings. He was described as “beautiful conformation, exquisitely proportioned with large hocks, well let down, with legs of iron, with unequalled lightness of forehand – a horse of incomparable beauty whose only flaw was being headstrong. An essentially strong stallion type, his quarters broad in spite of being half starved, tail carried in true Arabian style.”

But where did the Godolphin Arabian derive his name? After importing the horse from France, Edward Coke brought the horse to stud at his newly purchased farm Longford Hall in Derbyshire, England, where he stood until 1733. That year, at just 32 years old Edward Coke died unexpectedly, leaving his stallions including his “ye Arabian” to one friend, Roger Williams, and his mares to another friend and fellow horseman Francis, the second Earl of Godolphin. Not long afterwards the Earl of Godolphin also acquired the prized Arabian. It’s this owner that the horse was eventually remembered by.

The Earl of Godolphin moved the Arab and the rest of Edward Coke’s mares to his stud near Babraham in the Gog Magog Hills in Cambridgeshire, not far from Newmarket. One Arab’s first pairings with Edward Coke’s mare named Roxana produced one of the best racehorses of his time — a horse named Lath. The Godolphin Arabian also produced another prolific racehorse in Regulus. Regulus in turn produced Spiletta, dam to famed product of the Darley Arabian line, Eclipse.

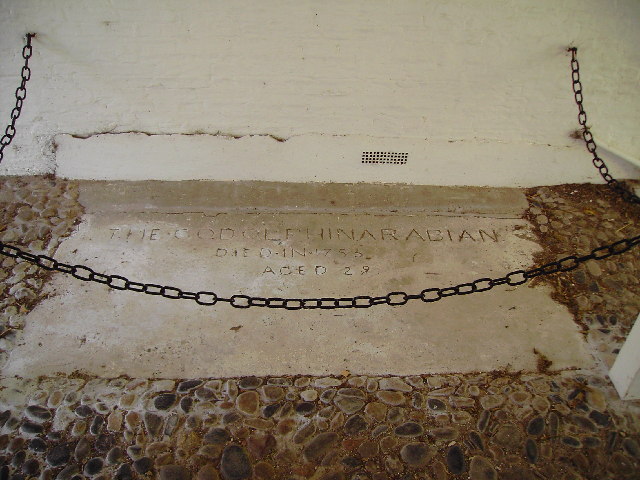

The Godolphin Arabian died in 1753 at an estimated age of 29 and is buried at the Earl of Godolphin’s former stable. His grave was marked by am inscribed stone slab that still lays inside the archway of the stable block today near Wandlebury.

The Godolphin Arabian’s contributions in the areas of speed and fierce competitiveness are evident in relatives like Seabiscuit and his match race rival, 1937 Triple Crown Winner War Admiral, distant cousins who are both related to the great Arabian. Many of the Godolphin Arabian’s offspring also played an influential role in the development of the Thoroughbred in America in the early 1700s.

During this era, what started as an oral tradition of telling the history of a horse at sale eventually led to a formal registration, including pedigree charts of each mating pair, so that breeding became exclusive to only horses whose lineage could be proven. This process effectively created the Thoroughbred and led to record books like the General Stud Book and the Jockey Club.

Honorable Mentions

In addition to the three foundation stallions another Arabian stallion from the 1700s left an indelible mark on the Thoroughbred as a breed — the Alcock Arabian, grandfather to all grey Thoroughbreds.

The Alcock Arabian, otherwise called Alcock’s Arabian or Pelham’s Grey Arab or Bloody Buttocks, was said to have been imported by Sir Robert Sutton from Constantinople but his history is questionable, much like the other foundation stallions, and he may have even been bred in England.

What is definitive is that he made it to England by 1704, eventually ending up in the hands of a man known only as Mr. Alcock in the General Stud Book who owned a farm in Lincolnshire, England. This became the horse’s namesake and the horse went on to become an influential stud in the early 1700s. In 1722 Mr. Alcock sold the stud to Peregrine Bertie, the second Duke of Ancaster. Later that year he died after producing just five recorded foals for the Duke.

Although his sire line is now extinct, the Alcock Arabian’s legacy is evident any time you see a grey horse at the track. The grey is a dominant gene and has the potential of passing down at least 50 percent of the time.

Legacy of the Foundation Sires

The legacy of the original foundation sires impacts more than just Thoroughbreds — believe it or not nearly all modern breeds can be traced back to Arabian, Turkish, or Barb origins according to this article published in Forbes Magazine in 2017,

In a study conducted by the University of Veterinary Medicine in Vienna, 50 horses of 21 varying breeds each had their DNA examined for Y chromosome and mitochondrial DNA similarities. Y chromosomes are passed through the male while mitochondrial DNA is passed through the female lines. The study revealed that selective breeding over the centuries has produced more genetic relatives than we might realize.

Such a strong emphasis on the original foundation stallions hundreds of years ago essentially created a lack of diversity in the variants of the Y-chromosome. Nearly all the samples included in the study could be traced within one 700 year old haplogroup that includes lineage from the Arabian Peninsula and the Turkoman horse, potentially even the Byerley Turk, Darley Arabian, or Godolphin Arabian themselves.

Which is where we’ll leave it to pick up in Part 3 of this series — how the Thoroughbred came to America and it’s influence on other modern breeds. Stay tuned and catch up on Part 1 here!

I am currently interested in any info I can get about the history of the thoroughbred. I am now the very proud owner of an OTTB who is proving to be a very capable dressage horse. I want to know his history and that of his forbears.

Hi Sondra! Congratulations on your new OTTB! If you’re interested in learning more about the early history and development of the Thoroughbred I really recommend checking out the book Speed and the Thoroughbred: The Complete History by Alexander Mackay-Smith. And if you haven’t already you should be able to find out your OTTBs breeding by searching on Equibase or All Breed Pedigree Databases. Enjoy the ride!