At the turn of the 20th century there were a handful of now iconic female figures emerging, many of whom still grace the pages of our history books – Helen Keller, Eleanor Roosevelt, Amelia Earhart, and Annie Oakley just to name a few.

And while many of us have no trouble identifying these 20th century feminist icons, there’s one name that is equally as legendary but far less known – Nan Aspinwall Gable, the first woman to ride solo across the continental United States by horse.

For whatever reason, Nan’s epic tale has been mostly lost to time even though the story of her award-winning journey was plagiarized by the “notorious equestrian travel charlatan, Frank Hopkins,” and served as the basis for the fictional horse movie Hidalgo. Regardless of those missing details, I’d like to share this story as completely as my research skills can manage because women like Nan Aspinwall Gable deserve to be remembered right alongside the greatest contemporaries of her generation.

One of the few resources that remain about Nan’s story is a thesis written by Mary Higginbotham in 2007 titled, In Genuine Cowgirl Fashion: The Life and Ride of “Two-Gun” Nan Aspinwall. It’s by no means the thrilling tale of adventure that you might expect but more of a biographical look at Nan’s life, piecing together the parts of her life and history that are left. This thesis has provided most of the references made in this article. A great deal of the information in this thesis was gathered from Nan’s own scrapbook, including many unnamed and undated newspaper clippings and photos that are now on display in the Nebraska History Museum.

The Birth of the “Montana Girl”

Nan Jeanne Aspinwall (sometimes known as Jennie) was born on February 2, 1880, in New York to Oliver Carpenter Aspinwall of Brookfield, Massachusetts, and Lena Kuetzing Aspinwall, originally of Berne, Switzerland. Shortly after Nan was born, her family moved west to the rural town of Liberty, Nebraska (population 74 as of 2017), where the family managed a general store. Her mother was a devout Christian Scientist and Nan inherited and wholeheartedly practiced her faith until she died in 1964.

In the days before television, traveling vaudeville shows were the epitome of entertainment and celebrity from the late 19th century leading into the the early 20th century. Two of the most famous of these traveling acts were Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West and Pawnee Bill’s Far East Troupe. These traveling troupes performed a variety of acts including exotic dancing (probably not exotic by today’s standards), rodeo events, sharpshooting, trick riding, singing and dancing.

By 1899, a 19-year-old Nan was performing with a vaudeville troupe as an exotic oriental dancer, “Princess Omene.” It’s quite possible that her faith played a large part as to why she would eventually abandon this character due to the seedy connotations of “dancers” in the early 20th century. But during her time on the traveling circuit Nan also met and married Frank Gable, a fellow vaudeville actor and roping expert who also hailed from the small town of Liberty, Nebraska. Her marriage to Frank may have also factored into her decision to move on from her dancing career. In 1906 Nan made her first appearance as a cowgirl – an image that was becoming popularized by Annie Oakley – and billed as a “Lariat Expert” alongside her husband Frank.

Nan and Frank continued their vaudeville careers and eventually joined Buffalo Bill and Pawnee Bill’s troupes where Nan made her debut as the “Montana Girl” – an expert horsewoman, trick rider, roper, and sharpshooter who wore a divided skirt and rode astride. She was the picture of the American cowgirl, according to the blog of author Nancy Leek.

She customarily wore typical Western wear: a divided skirt, boots, a silk or flannel shirt with a bandanna around her neck, and a Stetson hat. She had long blond wavy hair and an engaging smile. She claimed to have grown up on a ranch in Montana, where her father taught her to rope and ride. She looked every bit the Girl of the Golden West.

Nan, like Annie Oakley, was proof that cowgirls didn’t need to be born, they could be created. As part of this invented character, Nan told tall tales about her life as a ranch girl from Montana so convincingly that many newspaper publications would report her as being raised on a cattle ranch in the middle of Montana.

It was clear that performing with Buffalo Bill and Pawnee Bill carried some clout in terms of celebrity and towards the end of her life, Nan recalled to an Associated Press reporter, “I was the highest paid star in the troupe at $35 a week for the Wild West and Oriental parts of the show.”

Frank and Nan spent some time with Buffalo Bill and Pawnee Bill but eventually left to find success on their own. By 1910 they were running their own vaudeville act – Gable’s Road Show – with Nan and Frank at center stage.

The Ride of a Lifetime

But playing the part of an American cowgirl would not be the defining moment of Nan’s career. Nan was determined to live out the lifestyle she portrayed on stage.

Some accounts suggest that in starting their own show, Frank and Nan were looking for a way to publicize themselves when they came up with the idea for Nan to ride solo across America by horseback. Others say the trip was started as a bet between Pawnee Bill and Buffalo Bill, while others still suggest that the journey was a paid publicity stunt for a magazine or newspaper. Regardless of what actually prompted the trip, Nan embarked on a journey that would last 180 days covering 4,496 miles of harsh and undeveloped landscape between San Francisco and New York City alone.

She wasn’t the first person to attempt the solo trip but she would become the first woman ever to complete it.

In the weeks leading up to her departure from San Francisco, the Los Angeles Herald wrote:

“Miss Aspinwall is an experienced horsewoman, not only on the range but also with “Wild West” shows. She says she has no fear of accident to herself on the ride, but desires to secure a horse that will be able to stand the trip without mishap. “If I do not get the right kind of a horse soon,” said Miss Aspinwall yesterday at the Lankershim, “I will send to my father’s ranch In Montana and have one sent me from there. Of course, on a trip like this, I must have the best animal procurable—one that will make the trip and still look well when I arrive In New York city. Along the route, If people are interested In my stunt, I will give riding exhibitions. I would have issued riding challenges to women along the way if it were not for the fact that I am just recovering from a broken leg, which prohibits any such thing. However, I am always willing to meet any of my sex in a roping contest, and will issue challenges to that effect while en route.” Miss Aspinwall is only 24 years old [she was actually 30 and married], but has lived in the saddle practically all her life.”

Playing the part of her “Montana girl,” Nan was off in search of a horse that would be suitable for the 4,000 mile journey all while she was also recovering from a broken leg. She eventually settled on a Thoroughbred mare named Lady Ellen and left from the old San Francisco Chronicle building (609 Market Street) at 12:30pm on September 1, 1910, with her horse, her dog, and her gun at her side. Nan was off on her journey, carrying with her a letter from San Francisco Mayor Patrick H. McCarthy to be delivered to the Mayor of New York, William J. Gaynor, in Manhattan.

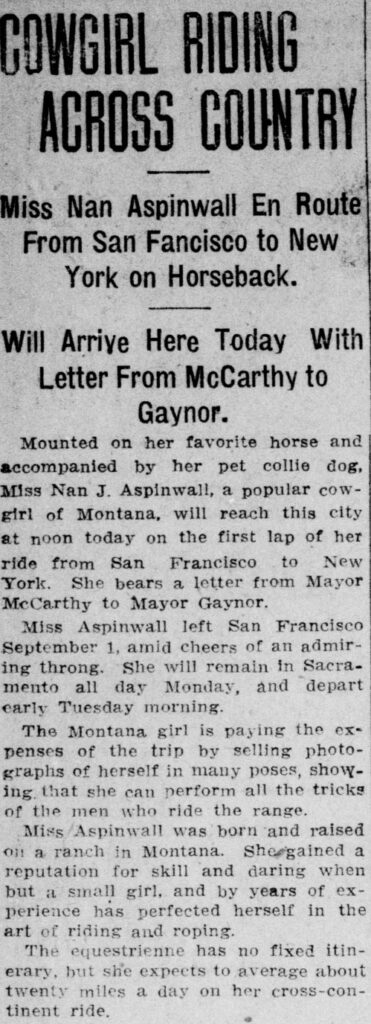

With her trip pre-dating the construction of both the Golden Gate Bridge and Oakland Bay Bridge in the 1930s, Nan started her journey making her way around the Bay Area, bound for Sacramento. The Sacramento Union published the following article on September 4, 1910, as Nan continued passing through the Bay Area. It claims she departed San Francisco amid the “cheers of an admiring throng” and details her fictional backstory and plans to fund her journey with shows and exhibitions.

Nan left San Francisco with only the bare essentials, refusing extra supplies, while her husband Frank rode ahead by train to scout the route and advertise her exhibitions. She was occasionally mailed supplies and extra clothing in advance of her arrival to a new city. With little in the way of maps or travel directions, Nan primarily followed the Western Pacific Rail Lines with great success until she ran into her first bit of trouble in Nevada.

After following a prospector’s trail that she thought was a shortcut through the woods, Nan became lost and disoriented in the mountains of Nevada during the late fall and early winter. She was forced to spend several days without food, water, or shelter in the wilderness alone as a result but managed to escape the situation with the instinctual help of her horse, Lady Ellen, who led her to safety after a few uncomfortable days.

She and Lady Ellen would develop a remarkable relationship that many newspapers viewed as the hallmark of a true cowgirl.

As her journey continued eastward from Nevada, she crossed the border into Utah shortly prior to October 31, where the Salt Lake Tribune published this article describing her days lost in the mountains.

MISS ASPINWALL REACHES ZION. Pretty Cowgirl Completes Ride from San Francisco to Salt Lake. TERRIBLE HARDSHIPS FAIL TO STOP PLUCKY RIDER. Lost for Day in Mountains, Without Food or Shelter, She Is Still Undaunted.

In zero weather with no shelter in the bleak mountains, no food for herself or her horse, she suddenly lost all sense of direction and for three days wandered helpless In the maze of the mountains. There were no trails, and she was forced to walk and lead her horse over mountain after mountain vainly searching for a trail. Finally she reached Proctor almost dead from exhaustion. Her shoes were worn from her feet and bleeding and fainting she stumbled into town.

When she arrived in Salt Lake she declares she presented a sorry spectacle. However, her trunks had arrived, and Saturday night Miss Aspinwall went to church wearing a broad Stetson crown to her tawny locks, a silk negligee man’s shirt, a natty divided skirt and a pair of substantial riding boots. She was certainly a type of the charming, dashing poster cowgirl.

Nan was the picture of the American cowgirl and certainly knew how to play the part. She crossed the Rocky Mountains through the Tennessee Pass in December 1910 near Mitchell, Colorado, and went as far as to (allegedly) shoot up the town just for the fun of it. She often slept in stalls or open fields along the way.

Newspapers rarely missed an opportunity to describe the traveling cowgirl. A recorded conversation between Nan and a Denver Post reporter helped paint the picture of a strong, independent woman.

Miss Aspinwall is a bundle of grit and determination such as is seldom found in femininity… “How were you regarded by the men on the trip?” was asked. “Oh all right. In many places they seemed afraid of me,” … “Did you leave a suitor behind?” Miss Aspinwall was asked. “Who–me? No,” she replied. “Then you’re not in love?” “Only with that mare of mine.” “Did you send home for money?” “No, and that’s why I haven’t got any of my ornaments with me now,” said the Western girl with a smile. “I earned my way…”

As she continued east through the winter, she made a stop in her former hometown of Liberty, Nebraska, in February of 1911 where the local paper referred to her as “the lariat girl” who’d attended school in Liberty for many years. She continued from Nebraska to Missouri through Kansas City in late March and on to St. Louis in early April.

In St. Louis, a newspaper asked Nan about her choice of a mount for the journey. She was steadfast in her choice of a Thoroughbred and seemed determined to prove her skeptics wrong. Nan was quoted as saying:

“It was Lady Ellen that saved my life. When I was getting ready for the ride everyone told me I wanted a bronc. I knew better. I wanted a Thoroughbred. An English magazine had negotiated with me to make the ride, but when I asked them to stake me to at least the price for horse feed they got cold feet. But I wasn’t going to be a piker, so I started on my own book. And I am going to finish the trip.”

Nan spent from April making her way from St. Louis through Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, and on to Pennsylvania and New Jersey by June of 1911. At this point Nan had covered more than 2,500 miles and was reaching a point of physical and emotional exhaustion. Newspapers and periodicals like the National Police Gazette were reporting on her movements, anticipating her arrival. This article from the Perth Amboy Evening News on June 11, 1911, recounts those difficulties just shy of a month prior to her arrival in New York City.

READY TO QUIT LONG RIDE

Nan J. Aspinwall, Cow Girl, in Pittsburg From Frisco.

Pittsburg, June 14 – “Nan” J. Aspinwall, “the cowboy girl”, who is riding from San Francisco to New York in horseback with a letter from Mayor P.H. McCarthy of San Francisco to Mayor Gaynor of New York, has arrived here exhausted.

“I wish Mayor Gaynor would jump on a horse and meet me halfway. I am an idiot for undertaking this trip, and I’d like to quit right here,” she remarked.

If history makes anything clear it’s that Nan Aspinwall was no quitter.

“I was told before I started out on this trip that I should do something startling if I wanted to get my name in the papers, and I am getting it all right.” – Nan Aspinwall, Pittsburgh Chronicle, June 1911.

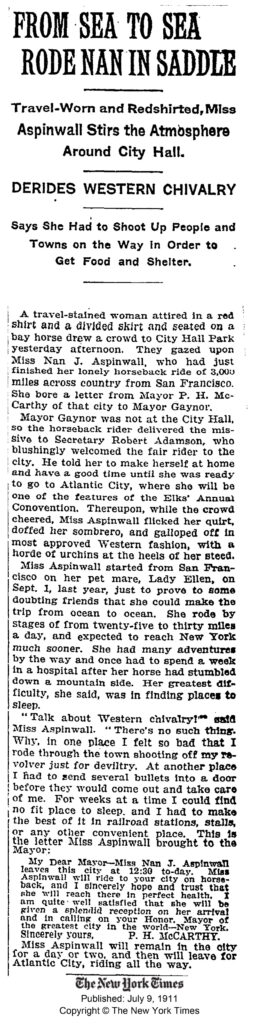

It took another 30 days from Pittsburgh to travel through the rest of Pennsylvania and New Jersey but on July 8, 1911, Nan Aspinwall, clad in her trademark Western attire, red silk scarf, stetson and split skirt, arrived in Manhattan and delivered the letter she was given in San Francisco to the private secretary of Mayor of Gaynor, Robert Adamson, at City Hall.

She’d spent 180 days on the trip, 7 of which were spent in the hospital after she and Lady Ellen rolled down a hill, and covered a total of 4,496 miles (even though to be totally fair I’m really unsure how that math works out, but again, this is what the research says) including an extra 400 or so that she spent lost.

In one of the most fascinating articles detailing Nan’s journey, the New York Times published this article on July 9, 1911, discussing her journey and arrival in New York as well as her plans to celebrate in Atlantic City, another 130 miles south of Manhattan that she would also ride with Lady Ellen.

“Talk about Western chivalry!” Nan said in the article. “There’s no such thing. Why, in one place I felt so bad that I rode through the town shooting off my revolver just for deviltry. At another place I had to send several bullets into a door before they would come out and take care of me. For weeks at a time I could find no fit place to sleep and I had to make the best of it in railroad stations, stalls, or any other convenient place.”

According to the New York Times article, “the horseback rider delivered the missive to Secretary Robert Adamson, who blushingly welcomed the fair rider to the city. He told her to make herself at home and have a good time until she was ready to go to Atlantic City, where she will be one of the features of the Elks’ Annual Convention…

According to the New York Times article, “the horseback rider delivered the missive to Secretary Robert Adamson, who blushingly welcomed the fair rider to the city. He told her to make herself at home and have a good time until she was ready to go to Atlantic City, where she will be one of the features of the Elks’ Annual Convention…

“Thereupon, while the crowd cheered, Miss Aspinwall flicked her quirt, doffed her sombrero, and galloped off in most approved Western fashion, with a horde of urchins at the heels of her steed.”

If that isn’t the most badass cowgirl moment you’ve ever read I want to know what the heck you’re reading. Seriously. Send it to me. Now.

Back on Stage and Death Valley Days

And so Nan’s journey ended almost as spectacularly as it began. She’d reached a certain level of celebrity and was awarded a medal from the National Police Gazette, meanwhile she and Frank were now wanted Wild West performers with opportunities that ranged from shows on the East Coast, to Europe and even South America. Whether or not she and Frank traveled that far is unknown, but they would both spent the rest of their lives working to capitalize on the success and fame of the cross country journey.

She earned the nickname “Two-Gun Nan” in the years following her ride, using the moniker on show posters across the country like this one below.

After several months celebrating, resting, and performing on the East Coast, the Gables eventually headed west again in late 1911. From 1911 to 1929 the Gables continued to play rodeos and vaudeville theaters in towns all over the country from Kansas City to Spokane. Nan would eventually settled down in Seattle, Washington, following Frank’s death in 1929. She toured a few shows in Southern California during the summer of 1930 but by 1931 she had retired from performing and donated Frank’s shooting equipment to the San Juan Basin Rife and Pistol Club in Durango, Colorado.

The last thirty years of Nan’s life were spent remarried and mostly in anonymity, save for a few Hollywood highlights. In 1942 her story was broadcast on Death Valley Days, a Western radio program and later television anthology series, and in 1958 a then 78-year-old Nan was invited to serve as a consultant on the Death Valley Days television series that ran from 1952 to 1970, for an episode loosely based on her life titled “Two-Gun Nan.”

In the twilight of her life, correspondence between Nan and her close family suggested that she again leaned into her faith after the death of her second husband. She left Seattle in 1954 and moved to San Bernardino, California, to be closer to her brother and would remain there until she died on October 24, 1964. Without any children of her own, the church seemed to provide some comfort for Nan in her later years.

According to her death certificate, Nan was a housewife for all her life. In truth we know she was anything but that.

9

Pingback: Long-form Writing Example: The Cowgirl Who Crossed America By Thoroughbred – Meghan Lalonde