One of the most undervalued aspects of a comprehensive equine education, in addition to having a solid understanding of basic horse anatomy, is being able to identify, diagnose, and treat common injuries. This is an especially useful skill when you’re horse shopping for ex-racehorses, including off track Thoroughbreds (OTTBs for the newbs) and off track quarterhorses (OTQHs).

You’ll often see in ads, “Clean legs.” “Sold sound with 30 day exchange policy.”

But what do you do when you can’t see the horse in person?

I didn’t end up with a sound, sane OTTB by accident. I ended up with the one I did because I relied on people who know what kinds of injuries most commonly happen to racehorses, which ones should be avoided, and what kinds of injuries are workable and manageable.

When you don’t have the education yourself, trust an expert. There is NO shame in that. And for the record, I am NOT a veterinarian. Pay for the pre-purchase exam (PPE) if you don’t have the experience or the help of an expert. But also know that if money is an issue, a PPE will significantly increase (and in some cases almost double) the cost or adoption fee. That’s something you need to weigh if you’re as crazy as I am and are looking at buying horses over the Internet sight unseen.

The first and perhaps most obvious indication of wear and tear is the number of times the horse was raced, when they were most recently raced, when they started their racing career and the speed and success with which they used to compete. While this is by no means a surefire way of picking a sound one, it’s a decent place to start as long as you also have a little context.

Example: Sure Prize, my boy, didn’t start racing until he was 5 years old. The Prize was unique in that despite starting racing at 5, he broke his maiden during his first year and only raced a total of 21 times over 3 seasons in racing. Most importantly, with a relatively low number of starts, the wear and tear of racing was put on after his legs and knees were closed and fully developed. Rather an unusual situation for OTTBs, but a fortuitous one for me.

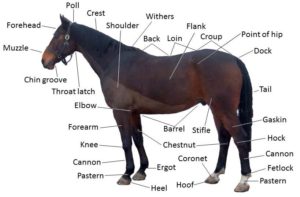

If you’re currently in the market for an off track Thoroughbred or off track quarter horse, here are the 10 most common injuries for ex-racehorses, but truthfully these injuries can happen to any horse. And while I’m sure more exhaustive medical lists exist, I’ll keep this as straightforward and easy to understand as possible so even the greenest of beginners can hopefully follow along. Refer to the horse anatomy picture for reference and trust in the magical powers of Google for everything else that I may not have answered.

1. BONE CHIPS

Bone chips can occur in nearly any joint on a horse, but most frequently in racehorses they occur in the knees or fetlocks. Technically referred to as osteochondral fragments, bone chips are essentially pieces of cartilage-covered bone (“osteo” for bone and “chondral” for cartilage) that have “chipped” off into a joint.

Causes: Kentucky Equine Research estimates that about 15% of horses have some form of bone abnormality that could result in a chip. In racehorses the most common causes of bone chips are rather obvious: being kicked/contacted by another horse at speed or stress to the joint due to training or conformation.

What to look for: Since bone chips typically occur in the joint, this is where you’ll need to pay close attention for any free floating little fragments. In my personal experience, owners are typically pretty forthcoming with this kind of injury since by the time the horse is ready for sale or adoption, there’s a good chance this injury has already been dealt with or assessed to some degree. You may also want to ask the owner to see radiographs or x-ray’s of the injury or injury post-surgery if they’re available.

Treatments: Some bone chips can be absolutely painless, while others can cause extreme pain, lameness, or even require surgery to remove. Typically bone chips should be removed as quickly as possible or as soon as they become detached.

Limitations & Prognosis: The size and location of the bone chip will dictate how much of an impact the injury will have over a long period of time. Even after bone chips have been removed you still have to be aware of cartilage damage and potentially arthritis in the affected joint. It doesn’t mean that horses with chips will be lame forever or limited in their careers. In fact it’s quite the opposite. Once chips are removed, in most cases ex-racehorses can move on to have successful second careers in dressage, eventing, hunter jumpers and just about every other discipline you can think of.

2. SPLINTS

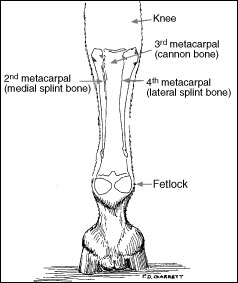

You’ll commonly hear this injury referred to as a”blown” or “popped” splint, and to understand why this happens, you also need to understand a little history and evolution of the horse. Way back in the days of the first horse, eohippus, the tiny creatures that grew into the horses we know today actually had toes rather than a single hoof on each leg. Today horses bear their weight on what would have been the middle toe, while the others have receded over eons of evolution into two supportive bones known as splint bones. The splint bones support each side of the cannon bone and taper down to an end about the fetlock of each leg. When splints are injured they typically swell and form bony enlargements that can be hot and cause lameness, and will typically leave a calcification,resulting in a hardened bump on their lower legs. Splints also tend to occur to younger horses between the ages of 2-5 years old, according to the University of Missouri.

You’ll commonly hear this injury referred to as a”blown” or “popped” splint, and to understand why this happens, you also need to understand a little history and evolution of the horse. Way back in the days of the first horse, eohippus, the tiny creatures that grew into the horses we know today actually had toes rather than a single hoof on each leg. Today horses bear their weight on what would have been the middle toe, while the others have receded over eons of evolution into two supportive bones known as splint bones. The splint bones support each side of the cannon bone and taper down to an end about the fetlock of each leg. When splints are injured they typically swell and form bony enlargements that can be hot and cause lameness, and will typically leave a calcification,resulting in a hardened bump on their lower legs. Splints also tend to occur to younger horses between the ages of 2-5 years old, according to the University of Missouri.

Causes: Splint injuries are typically caused by trauma, strain, or a tear of the interosseous ligament, which helps attach the splint bones to the cannon bone. Popped splints can also be caused by direct concussions or kicks to the splint bones and conformational biases as well..

What to look for: A horse with a splint injury or past splint injury will present with a bump on their splint bone. This bump can be hot or cold depending on when the injury was sustained.

Treatments: Treating a splint requires rest, just like many other injuries. The goal of this period of rest is typical to reduce swelling and minimize the bony swelling with icing, cold hosing, or similar therapy to decrease swelling. The more inflammation that can be taken out, the less severe the final blemish will be.

Limitations & Prognosis: Fortunately for anyone undeterred by superficial blemishes, blown splints are one of the few injuries that almost always result in a full return to work. For this type of injury the prognosis according to TheHorse.com is good to excellent, except for cases in which the bony growth is unusually large and interferes with the knee joint or suspensory ligament. For the most part, however, splints are curable, manageable, and recoverable.

3. BOWED TENDONS

While many people think that bowed tendons or tendinitis is an injury reserved for racehorses, it’s something that can happen to any horse almost at any time. Simply put, a bowed tendon is the inflammation or enlargement of the superficial deep digital flexor tendon located directly behind the cannon bone in a horses lower leg. The severity of the injury depends on how much and how deeply the tendon or tendon sheath has been torn.

Causes: Bowed tendons are commonly caused by a severe strain or injury in one of an ex-racehorse’s front legs. This could happen during a race or training, or like many other injuries, even during transport or turnout.

What to look for: A horse that has a bowed tendon will quite literally present with a curved or slightly bowed tendon behind the cannon bone. While this injury tends to happen to older horses, it can happen to younger ones too. When the injury is initially caused, bleeding from the tear will cause the swelling and also create heat. What may or may not occur is acute lameness. According to the American Association of Equine Practitioners, many horses with serious tendon damage never exhibit lameness. If you know that a horse has sustained a tendon injury, you might also be able to ask for ultrasounds.

Treatments: Like just about any injury, a bowed tendon isn’t a fun one to deal with. Ice and cold hosing as well as wrapping or poulticing the affected leg should help prevent swelling and inflammation, but it’s also recommended that horses with bowed tendons go on stall rest for anywhere from 6-12 weeks depending on the severity. Confinement and a controlled exercise / hand walking program is the best way to encourage healing of the tendon while also preventing another injury. Tendon rehab is known to be a long and tedious ordeal so this is one that if it happens to your horse, contact your vet to discuss a plan.

Limitations & Prognosis: As I mentioned, tendon injuries are known to be a long and tedious process, usually one that can take anywhere from a few months up to a year in some cases. More importantly, as the tendon heals, the scar tissue that replaces the torn fibers of the tendon tend to be much less elastic than the original tissue, meaning that you might need to be cautious of re-injuring if you’re doing more upper level or jumping type work.

4. Condylar Fracture (fracture in the fetlock)

Any fracture isn’t a great situation. A condylar fracture, explained simply, is a long, vertical fracture to the lower end of the cannon bone (third metacarpal). When most people hear about any kind of fracture, meany think that it’s a career-ending, not to be ridden again sort of ordeal. Truth be told that’s not actually the case for many. Even some racehorses return to the track after having recovered from this injury.

Causes: Stress, conformational bias. Concussion to the weight bearing cannon bone that can initially result in micro damage or a complete fracture. This kind of fracture is among the most common long bone fractures in horses, especially OTTBs, and can truly happen for a number of reasons, including pathologic fractures, which occur when a bone is weakened by disease, infection, osteoporosis, etc., or repetitive strains that happen during high speed exercises and place a large load on this weight-bearing bone.

What to look for: This sort of fracture to a weight bearing bone will almost certainly cause lameness in the affected leg. As an OTTB buyer, this also means a few things – first, that by the time the horse is available for sale it’s very likely this is something that will have either been surgically repaired or that it’s something that the buyer should disclose and hopefully be able to provide you with some x-rays or MRIs.

Treatments: Treating condylar fractures is another long and tedious process commonly involving several months of time off and/or stall rest. In many cases surgical repair of condylar fractures place screws in the cannon bone after the fracture has been aligned with the parent bone. This procedure is something that typically most experience equine surgeons can do with the help of radiography or fluoroscopic control.

Limitations & Prognosis: This is another serious injury that depends significantly on the severity and placement of the fracture for any buyers who are upper level eventers and jumpers. However, depending on the particular horse’s recovery and career, you may very well find that the injury was a one off and that he or she has since gone on to race successfully without experiencing this injury again. On the flip side you may find that this injury has happened multiple times in multiple legs. This is often a workable injury for many riders but is typically best suited for lighter workloads.

5. STRAINED SUSPENSORY LIGAMENTS

The University of California – Davis School of Veterinary Medicine and Center for Equine Health conducted a survey of horse owners in 1999 and second to colic, injuries to the suspensory ligament were the next most common. The suspensory ligament is a strong band of tendon-like tissues behind the cannon bone that plays a critical role in supporting the fetlock preventing excessive extension of the joint during all weight-bearing contact, stances, and strides. You’ll commonly hear this injury referred to as a “dropped suspensory ligament” because of the way the ligament appears to “drop” and stretch below the fetlock, down to the pastern.

Causes: Tears to the suspensory ligament can occur due to strain from working in deep footing, fatigue, age, hyperextension or improper training.

What to look for: Signs of this injury, like many, will vary depending on how recently the injury occurred. If it’s a recent suspensory injury, the horse will very likely exhibit lameness, swelling, and heat in that leg. If the injury is cold and healed it’s possible the ligament will remain stretched, but not painful.

Treatments: Just like humans, ligaments heal slowly and tend to heal with stiffer, less stretchable scar tissue in place of the damaged tissue. This means that for many tendon injuries it’s critical to develop a solid rest and rehabilitation program so you have adequate time to assess the severity of the injury and allow for healing time as well. Stall rest and cold hosing is typically recommended to initially treat this injury. Once approved by a vet you’ll be able to slowly ease your horse back into work, beginning with lots of hand walking.

Limitations & Prognosis: Again this depends on the severity of the individual injury but some horses with less severe injuries may be suitable for all types of work, including returning to racing. Other more severe suspensory ligament tears can mean that the horse will only be suitable for light pleasure riding, even with a successful rehabilitation period.

6. OSSELETS (Arthritis of the fetlock)

Osselets is just another horse word for arthritis in the fetlock, most commonly caused by stress or trauma between the cannon bone and large pastern bone at the front of the fetlock. Typically osselets occur in a horse’s front legs because of the increase strain and concussion at high speed.

Causes: Young OTTBs, OTSBs, and draft horses, are the most common victims of osselets. Osselets are caused by trauma or stress, resulting in stretching of the joint capsule that can be hot, soft, and swollen which may lead to permanent or chronic damage to the cartilage within the joint.

What to look for: Osselets will present with swelling or inflammation at the fetlock. Depending on the when the injury occurred the swelling may be hot or cold and set. Horses with short upright pasterns are also particularly predisposed to developing this sort of injury.

Treatments: A combination of reduced work and cold therapy is recommended if the osselets are swollen and hot for an initial period of at least 48 hours. This will help reduce any inflammation and acute irritation in the fetlock. Following this period of cold therapy, heat therapy techniques can also be applied with warm compresses, warm water hosing or whirlpool baths (for the rich and fancy), alternating with applications of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or casaicin, all at the advice of your veterinarian.

Limitations & Prognosis: Unlike many more severe injuries, osselets don’t have to be a career ending or even career limiting kind of injury. Once calcified, most osselets are painless and after about 4 to 6 weeks of treatment the horse stands a good chance of a complete recovery and return to work.

7. SESAMOID FRACTURES

At the back of a horse’s fetlock sit two small bones — the sesamoids. These bones anchor the suspensory system and fetlock and absorb a tremendous amount of pressure each time a horse takes a step. Because of the weight-bearing nature of these bones, injuries to them can range from mild to catastrophic and unrepairable. Fractures to one of the proximal sesamoid bones are classified according to their location — apical, mid-body, basilar, abaxial, axial or comminuted. For more information on those types of fractures you can find more scientific details here.

At the back of a horse’s fetlock sit two small bones — the sesamoids. These bones anchor the suspensory system and fetlock and absorb a tremendous amount of pressure each time a horse takes a step. Because of the weight-bearing nature of these bones, injuries to them can range from mild to catastrophic and unrepairable. Fractures to one of the proximal sesamoid bones are classified according to their location — apical, mid-body, basilar, abaxial, axial or comminuted. For more information on those types of fractures you can find more scientific details here.

Causes: Similar to other fractures to a weight-bearing bone, a sesamoid fracture can occur due to trauma, concussion, and tend to happen at the end of a race or workout when a horse is fatigued.

What to look for: A sesamoid injury will almost certainly bring on lameness as a result. As an OTTB, OTSB or OTQH buyer, this also means that by the time you’re looking at them they’ve probably already recovered or had a veterinarian at least assess this issue so you’ll want to ask for x-rays or any other documentation about the injury if the horse you’re looking at appears to have this kind of injury. You’ll also want to be aware that because the suspensory system is attached to the sesamoids, the suspensory ligament is often involved in this injury.

Treatments: Some sesamoid injuries, as I mentioned, can me catastrophic. Simply put the bone can be broken into more pieces than can possibly be put together with surgery. While this is indeed a worst case scenario, other less severe cases may still require surgical intervention. The severity and location of the fracture will also have an impact on the type of treatment necessary.

Limitations & Prognosis: The sesamoids don’t receive the best circulation and because of this, healing often takes a lot of time and patience. If the horse has come back from successful surgery, it’s quite possible they can go on to have successful careers in most disciplines including dressage and hunter jumpers.

8. BUCKED SHINS

Bucked shins is the horseman’s way of saying that there’s some inflammation of the tissue that covers the cannon bones. This injury happens most commonly in young horses during early training. According to the Merck Veterinary Manual, bucked shins can also be part of a disease complex known as dorsal metacarpal disesase.

Causes: Repeated concussion, high strain and fatigue, commonly in racehorses.

What to look for: With any horse that has an old or new bucked shin, you’ll notice some swelling or inflammation on the front of the cannon bone.

Treatments: Like any inflammation, bucked shins can be treated with ice packs, cold hosing, or cold compresses. New therapies involving algae have also been tested, according to Kentucky Equine Research, as recently as 2017.

Limitations & Prognosis: Once inflammation has subsided or once the injury is cold and hardened, it’s most likely the horse will be able to return to competition level.

9. BOG SPAVIN

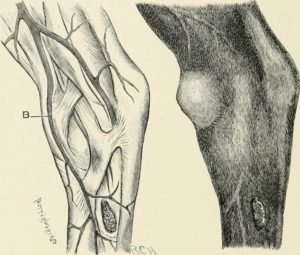

Bog spavin is a cosmetic blemish of the hock area, similar in appearance to windpuffs. This alone does not usually cause lameness although the joint may be swollen or filled with fluid. Swelling is caused by inflammation of the joint lining with increased fluid inside the joint. The swelling should be able to be seen and felt at the front towards the inside of the hock.

Bog spavin is a cosmetic blemish of the hock area, similar in appearance to windpuffs. This alone does not usually cause lameness although the joint may be swollen or filled with fluid. Swelling is caused by inflammation of the joint lining with increased fluid inside the joint. The swelling should be able to be seen and felt at the front towards the inside of the hock.

Causes: Bog spavin can be caused by poor conformation, severe injury or strain to the hock, or by quick stop and turns with weight on the rear. Nutritional deficiencies can also be a contributing factor to bog spavin.

What to look for: A horse with a bog spavin will exhibit some signs of swelling that should be visible and felt at the front towards the inside of the hock. In some cases this swelling may be hot or painful.

Treatments: This is one of the few injuries that tends to heal on its own, leaving the horse with a small, painless swelling that may eventually disappear altogether or be able to be drained by a vet. However in severe cases anti-inflammatory drugs can help prevent inflammation and fluid build up, and in others surgery using an endoscope might be necessary.

Limitations & Prognosis: A bog spavin is not the same thing as arthritis an for that reason, this injury typically isn’t a very limiting one. It is however an indication that arthritis, tendinitis, or other joint related issues might be on the horizon. Depending on a horse’s age, this might not be a problem or it may be a deal breaker for those in the market for an upper level eventing prospect or show horse.

10. SWOLLEN KNEES

The knee is a complicated joint and any swelling in a horse’s knee can be cause for concern. Whether the joint is just bruised or has recently experienced trauma to the area, without diagnosis from a vet it’s going to be difficult to determine the underlying issue. Those underlying issues can include a soft tissue injury, acute inflammation (carpitis), or oseoarthritis.

The knee is a complicated joint and any swelling in a horse’s knee can be cause for concern. Whether the joint is just bruised or has recently experienced trauma to the area, without diagnosis from a vet it’s going to be difficult to determine the underlying issue. Those underlying issues can include a soft tissue injury, acute inflammation (carpitis), or oseoarthritis.

Causes: Swollen, fractured, or otherwise damaged knees can be caused by poor conformation, repeated concussion, or severe trauma.

What to look for: This injury should be rather obvious — the knee will be swollen, possibly hot and potentially painful.

Treatments: the treatment for swollen knees depends on the underlying issue. Depending on the severity of the issue will determine the course of treatment. For some less serious trauma, icing or cold hosing will address local inflammation and swelling while more serious issue including fractures will almost indefinitely require surgery and extended periods of stall rest.

Limitations & Prognosis: Again, the final prognosis of this injury will depend on the accurate diagnosis and treatment of the underlying injury. If the injury is as severe as a fracture or something that require surgery, chances are the horse will be able to return to work but at a reduced workload. Other less severe injuries may require ongoing monitoring or the addition of joint supplements.

This article is intended for informational and educational purposes only. As I mentioned earlier in this novella, I am not a veterinarian so please and as always, consult with your preferred equine healthcare provider before relying on this information for diagnosis or treatment.

1